Anyone who takes a walk around Copenhagen is bound to run across one of the hundreds of concrete bunkers that were built to defend Danes from air raids during World War II.

There are a couple in the park near my house, huge slabs of grey concrete now partially covered by greenery. Many of the interiors have been renovated, and the bunkers are very popular with up-and-coming rock bands, who use them as soundproof rehearsal halls.

The bunkers were never used for their intended purpose.

The German occupying force rolled in by land, and Denmark surrendered almost immediately – the flat Danish landscape would have been no match for the powerful Nazi tank divisions of 1940. Denmark was occupied for more than 5 years.

Tomorrow evening – Monday, May 4, 2020 – many Danes will put a candle in the window to mark the 75th anniversary of the end of that occupation.

Here come the trolls

Even before the anniversary, I’d been thinking a bit about Denmark’s history during World War II.

One reason is that a group of Chinese Communist Party trolls has been on social media mocking Denmark’s “lack of honor” after the Nazi invasion.

Their messages, on networks blocked for the average Chinese citizen, seem to have been centrally coordinated and are almost certainly fruits of the CCP propaganda machine, no doubt in response to a Danish newspaper’s cartoon satirizing the Chinese origins of the coronavirus.

“The country that surrendered to the Nazis in a few hours has now surrendered to the virus!” wrote one lovely fellow after Denmark reported its first coronavirus casualties. “The spineless Danes surrendered to Nazi Germany in just four hours!” wrote another.

Why anyone in the Chinese government thought this would help achieve their diplomatic goals is a mystery.

“Thanks for the time you spent with us”

The second reason is that during the coronavirus lockdown, I’ve been exploring local parks.

One in Northern Copenhagen is called Mindelunden – in English, Ryvangen Memorial Park –

and it’s the final resting place of the members of the Danish resistance who were executed nearby.

Many Danish cemeteries, such as Nørrebro’s famous Assistens Kirkegaard, are casual places that welcome picnics, lunches, and sunbathers, but not this one.

Mindelunden is quiet and carefully fenced-in with watchful caretakers (I accidentally rode a bike in the first time I visited, and let’s just say they were not pleased) and it is full of memorial bouquets, even apart from official holidays.

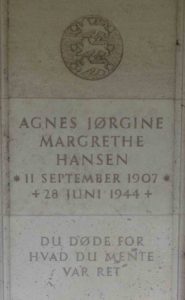

A female resistance fighter’s grave, with the legend “You died for what you thought was right.”

It’s moving to see the graves of the resistance fighters, many of whom were very young when they were executed – there are several 17 and 18-year-olds.

(“Thanks for the time you spent with us,” reads the gravestone provided by the family of one teenager.)

Older resistance fighters have gravestones that list their occupation – merchant, editor, engineer. There are a few women, but not many.

It’s upsetting to see how many of the executions took place in the very last days of the war, during March and April 1945.

Even the German soldiers carrying out their orders must have known that theirs was a lost cause by that point.

.

Friendly with Germany

Interestingly, I don’t see much tension between Denmark and Germany these days. Problems in Germany produce none of the barely-disguised glee apparent in the Danish media whenever anything goes wrong in Sweden.

Many Danish children still learn German in school – in some places, it’s required – and the west coast of Denmark is deeply dependent on tourism from Germany.

The Germans rent summerhouses on the west coast, shop and eat in restaurants there (you can count on every menu being available in German) and enjoy the windy, chilly beaches.

Along those beaches are another set of bunkers, increasingly laid bare as the white sand shifts. There are dozens if not hundreds of them, many open for visits and popular with tourists. These are the bunkers constructed by the Germans during their occupation, defenses against an Allied naval attack that never came.

Seventy-five years later, what happened in 1940-1945 has been neither forgiven nor forgotten, but it has been set aside in the postwar spirit of inter-European co-operation.

It seems likely that when the Danish borders open again after their coronavirus closure, the first foreign tourists admitted will be German.