I help out at a flea market sometimes near Copenhagen, a flea market that’s held a few times a year to benefit my daughter’s marching band. We sell things people have sent for recycling – at the local recycling center, you can put things that are still useful in a special room, and then community groups sort through those things and sell them to raise money.

We have one persistent problem: too many shotglasses. Each new week brings dozens of beautiful crystal shotglasses, prized for a lifetime by someone from the older generation, perhaps now the dead generation. These people to used to drink clear snaps before fancy Easter lunches, and or a dark bitter alcohol called Gammel Dansk before breakfast.

People in Denmark don’t do that much any more. They go jogging before breakfast and drink wine for holiday lunches, if they drink anything.

And most young people already have a set of grandpa’s old shotglasses gathering dust somewhere at the back of a cabinet, and they don’t need any more.

So week after week, these lovely little etched crystal glasses line up like fragile soldiers on the storage shelves at the flea market. Nobody needs them, nobody buys them, but we just don’t have the heart to throw them out.

The death of the little corner shop

Every country changes, and so does Denmark. When I hold How to Live in Denmark events, people often ask me how Denmark is changing, or has changed since I got here fifteen years ago. I could name a hundred things, but the first one that always comes to mind is food and drink.

Shotglasses are out, snaps and Gammel Dansk is out, fine wine (almost always bought on sale at the supermarket) is in.

The small food stores that used to be on every corner in Denmark – the ‘pålæg’ or sausage shop, the fish shop, the dairy shop – are out. There used to be an odd type of Danish store called a kolonial, which sold canned goods and dry goods, basically stuff from the old Danish colonies in Africa, India and the Caribbean.

That’s out too. Supermarkets are in.

All the shops were closed on Sunday

In some ways, this is a good thing. When I got here, fifteen years ago, all the stores in Denmark closed early Saturday afternoon and were closed all day Sunday, too, except for one ragged little shop in Copenhagen train station. (That little shop saved a lot of Sunday dinners.)

Now the big supermarkets are open all week, and most evenings. And so is the new breed of food specialty shops, mostly bakery chains.

I have to admit that these new trendy bakeries are pretty good. Actually, they’re a lot better than the dusty little independent bakeries that used to be open on every street corner, usually serving flat croissants and stale pastries.

The pastry worth waiting an hour for

My favorite bakery chain is called Lagekagehus. When I first arrived here, Lagekagehus was a single bakery in the Christianshavn neighborhood of Copenhagen. People would come from far and wide to buy bread and pastry there. Sundays it was so crowded that you had to take a number and stand in line for an hour sometimes to get a loaf of bread or some pastry. It’s excellent pastry, but come on!

Anyway, a private equity fund ended up buying that single bakery, and now there are dozens of Lagekagehuse, including two at Copenhagen airport and one at the main train station. And they’re still as good as the original.

Problems with hand food

I wish someone would make a chain for traditional Danish håndmad, or hand-food, the little open-faced sandwiches also known as smørrebrød. This is the traditional lunch of the Danish working class. Hand-food is still sold at a few little corner shops that open at 7 in the morning, when painters and plumbers and other people who work with their hands are on their way to work.

These little smørrebrod shops are usually run by large, cheerful ladies who do all the cooking and slicing themselves. They have only a limited number of sandwiches per day – when they’re gone, they’re gone. They don’t make any more. In fact, the shops usually close at 1 or 2 in the afternoon. And the ones near me will only take cash. I love smørrebrød, and I would eat a lot more smørrebrød if these shops didn’t make it so bloody difficult.

But I see fewer smørrebrød shops than I used to, and a lot fewer bodegas.

A bodega in Denmark is a type of bar, a little bit like British pubs, only darker, and smokier, and usually populated by the old, and the poor, and the disabled. Maybe a few random hipsters, or some working-class guys or gals having a beer after work.

Bodega windows are covered with yellow glass or heavy red curtains so you can’t see in from outside. They tend to serve flat beer in scratched glasses, or wine that tastes like the bottle has been open for a couple of days.

Bodegas for the lonely

Yet I like bodegas, because they’re a place for people who might otherwise be lonely to hang out and enjoy some togetherness. If poor and displaced Danes didn’t have a bodega to hang out in, I’m sure the Danish state would end up creating some day center for them to hang out which would be basically the same except for the alcohol. That said, I don’t see any private equity funds creating a chain of bodegas anytime soon.

There are other changes, too, since I arrived. You can really see the impact of digitalization: there are very few paper newspapers in Denmark these days, very few letters and hardly any postboxes, and not much paper money.

And in general, you can also see that Denmark has become more prosperous. It was common fifteen years ago to see apartments with that had toilets in the hallways, and a few houses that still relied wood or coal stoves, but you don’t see that much any more. As a matter of fact, a very old shop in my neighborhood selling wood and coal, run by a very old man, just went out of business.

And, of course, Denmark has clearly become a more multi-cultural society over the past 15 years.

At the flea markets, I find myself selling a lot of sets of plates and cups and kitchenware from recently deceased Danes to new arrivals – sometimes, students, sometimes refugees – people like I was 15 years ago, people who are just setting up households in Denmark.

They need everything: chairs and tables and pots and pans. They only thing don’t seem to need is shotglasses.

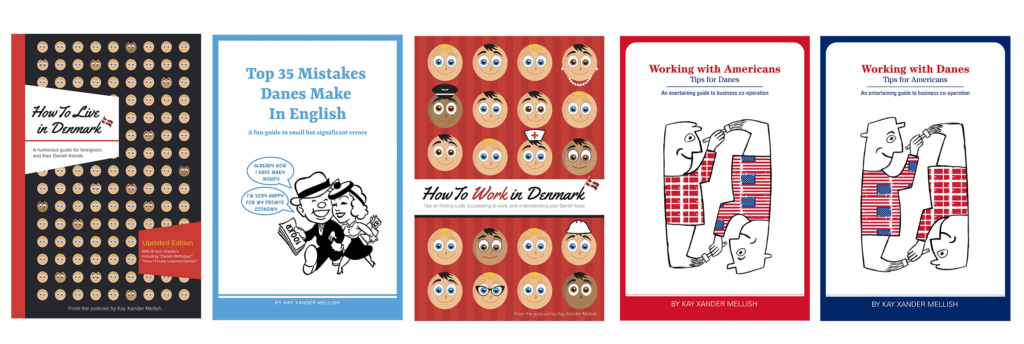

Buy Kay’s books about Denmark on Amazon, Saxo, Google Books, Apple Books, Barnes & Noble Nook, or via our webshop.

Image mashup copyright Kay Xander Mellish 2025